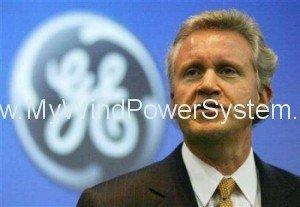

Last year, there were forecasts that electricity generated from nuclear plants would be cheaper than, or about the same price, as natural gas. But Jeff Immelt now says no. And he should know- he’s the CEO of GE!

Jeffrey R. Immelt is the ninth chairman of GE, formerly General Electric, the atomic/nuclear industry pioneer. He is no newcomer- it’s a post he has held since 2001.

“It’s really a gas and wind world today” he said.

“When I talk to the guys who run the oil companies they say look, they’re finding more gas all the time. It’s just hard to justify nuclear, really hard. Gas is so cheap and at some point, really, economics rule, so I think some combination of gas, and either wind or solar … that’s where we see most countries around the world going.”

Mr Immelt said this an interview to the heavyweight economic newspaper, the Financial Times recently.

Market prices for solar panels have plummeted, wind turbine prices have declined and large finds of shale gas have prompted hopes that the low gas prices in the US could spread. All this means that the future is likely to be a mix of gas, wind and solar power.

However Steve Kidd, deputy director-general of the World Nuclear Association, sees hope on the horizon for nuclear power.: “Cheap gas prices make it difficult for new nuclear plants to compete economically but we would question the likelihood of these price levels continuing much longer and their relevance to the situation elsewhere in the world.”

But the context is of Lengthy delays in building the two first nuclear reactors to be built in Europe for twenty years. These are at Olkiluoto, Finland, and the Flamanville project in France. These delays have pushed up estimates of nuclear reactor costs. Indeed some countries, such as Germany, have abandon nuclear power.

Olkiluoto 3 in Finland was supposed to have entered service three years ago. But it has been repeatedly delayed, leading to more than €2bn of cost overruns. It will take another three years to complete.

The cost of the Flamanville 3 1.65GW reactor in northern will not commence generating for another 3-4 years and its budget has grown from €3.3bn to €6bn.

When the “nuclear spring” revival was occurring in 2007 and 2008, companies were expecting much higher power prices, thus making the heavy investment needed seem less risky. It was also forecast that there would be higher carbon prices, which would put coal and gas-fired plants at a disadvantage to nuclear and renewables.

In many developed countries recession has kept demand for energy and power prices lower than expected, making the conditions for nuclear investment less favourable. Indeed, because of the massive investment needed and the construction risks involved, as illustarted in France and Finland it is unlikely that the private sector will be willing to fund new nuclear plants without subsidies and incentives from governments. And of course, the globasl recession means that governments have little in their coffers.

This all points to wind power and solar power being the main carbon-free sustainable sources of electricity generation for the future, not nuclear power.